9/13/12

Chapter 8

Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndromes

J. M. Barker and G. S. Eisenbarth

Examples of Polyendocrine Autoimmune Syndromes include:

1. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type I1 2, 3(APS-1, APECED: autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy, MIM number 240300[Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man)

2. The autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type II (APS-2, Schmidt’s syndrome MIM number 269200) 4-6 7

3. IPEX (Immunodysregulation, Polyendocrinopathy and Enteropathy, X-Linked), also termed XLAAD X-Linked Autoimmunity Allergic-Dysregulation Syndrome or XPID X-Linked Polyendocrinopathy, Immune Dysfunction and Diarrhea, MIM number 304790 and 300292)

4. Non-organ-specific autoimmunity (e.g., lupus erythematosus) associated with anti-insulin receptor antibodies8, 9

5. Thymic tumors with associated endocrinopathy10-13, 13

6. Graves’ disease associated with insulin autoimmune syndrome14, 15

7. POEMS syndrome (Polyneuropathy, Organomegaly, Endocrinopathy, M-spike, Skin changes MIM 192240)16, 17

8. Congenital rubella infection followed by development of thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes +/- other autoimmune disorders.

9. Anti-Pit1 Antibody: Adult combined GH, prolactin and TSH deficiency.

The diverse names given to the polyendocrine autoimmune syndromes reflect the large number of studies and case reports concerning these patients and heterogeneity in their clinical presentation. The two major autoimmune endocrine syndromes, APS-1 and APS-2, both have Addison’s disease as a prominent component. The major autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes have a strong genetic component with the type 2 syndrome occurring in multiple generations and the type I syndrome in siblings.

The major illnesses associated with both APS-1 and APS-2 are listed in Table 8.1 and differences between the syndromes are outlined in Table 8.2. Knowledge of disease associations and inheritance pattern facilitates early diagnosis of component illnesses7. Patients with APS-1 and APS-2 develop multiple diseases over time and approximately one out of seven relatives of such patients have an undiagnosed autoimmune disorder (most often hypothyroidism for the type 2 syndrome)18. The individual polyendocrine autoimmune syndromes, their immunogenetics, pathogenesis and selected aspects of therapy will be reviewed in this chapter.

Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndrome Type 1 (APS-1)

Major components of the APS-1 autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome (also termed APECED autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy 19-22 include hypoparathyroidism23-25, mucocutaneous candidiasis26-28, and Addison’s disease (Table 8.1). Other diseases associated with APS-1 include autoimmune hepatitis29 primary hypothyroidism, a malabsorption syndrome30, 31, vitiligo, pernicious anemia32, type 1 diabetes, alopecia33, primary hypogonadism34, cutaneous abnormalities1, pulmonary disease35, 36, ovarian failure37, 38, pericarditis39, cerebellar degeneration40, encephalopathy41, asplenia42, esophageal cancer43, polyneuropathy44, pure red cell aplasia45, 46, etc. Of note, in a study by Friedman and coworkers47 four of nine patients with APS-1 were asplenic.

An unusual manifestation of the disorder is the development of refractory diarrhea/obstipation that may be related to “autoimmune” destruction of enterochromaffin or enterochromaffin like cells, associated with specific autoantibodies48-50. Kampe and coworkers have reported that antibodies to Histidine Decarboxylase are associated with a history of intestinal dysfunction51 and multiple reports document loss of gastric and intestinal endocrine cells 51 including chromogranin A and serotonin producing cells50. A number of rare manifestations of APS-1 are particularly troublesome. A number of patients have been reported with severe lung disease, often leading to death. The lung disorders have been described as autoimmune bronchiolitis, bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis19, 35, 52. Patients are at risk for developing esophageal and oral cancers presumably related to chronic candida infections43.

The onset of the disease is usually in infancy. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis is often the first disease detected, followed by the later development of adrenal insufficiency. The etiology of the mucocutaneous candidiasis in the absence of systemic candidiasis in the APS-1 syndrome has been related to anti-cytokine autoantibodies (anti-IL17A, IL17F and IL22) related to Th17 T cells 53 and depressed production of IL17F and IL22 by peripheral blood mononuclear cells 54 through increased IL17 with decreased IL22 also reported26. Decades may elapse between the diagnosis of one disease and another in the same individual and the order of disease appearance is not invariant. There is a remarkably strong association with autoantibodies targeting interferon alpha and omega which are “diagnostic” except for the additional association with thymomas with such autoantibodies13, 55.

The syndrome is almost always inherited in an autosomal recessive manner linked to mutation of the AIRE gene 56 57(AIRE: Autoimmune Regulator gene) on chromosome 2158; 59. The immunodeficiency underlying disease susceptibility is secondary to autosomal recessive mutations of this transcription factor60. Studies of autoimmune disorders including Addison’s disease, but in patients without the APS-1 syndrome, indicate that AIRE mutations are not involved in these more common diseases61. In contrast, there is evidence that in rare diseases with abnormal T cell development (e.g. T-B-SCID, 0menn syndrome (OM1M 603 554) there is abnormal thymocyte epithelial interaction and deficient thymic AIRE and lack of expression of AIRE dependent “peripheral” molecules such as insulin 62. There is no association of the overall syndrome with specific HLA class II alleles, though there is increasing evidence that specific HLA alleles determine the probability of the specific organs targeted by an individual63. In particular DQB1*0602 appears to protect from type 1 diabetes and DR3 increase the risk of type 1 diabetes in patients with the APS-1 syndrome, as it does for the common variety of type 1A diabetes.

The knockout of the AIRE gene by two groups in mouse models indicates that mice lacking AIRE develop widespread but clinically mild autoimmunity. In particular autoantibodies reacting with multiple organs and T cell infiltrates of multiple organs are observed 64, 65. A potentially very important finding is a decrease in expression within the thymus of what have been termed “peripheral antigens”65. Hanahan and coworkers coined the term peripheral antigen expressing cells, for cells within the thymus that express “Peripheral” molecules such as insulin66.

It is now apparent that multiple such molecules are expressed within subsets of cells within the thymus, with relatively few cells expressing any given molecule, but many thymic cells expressing multiple different “peripheral antigens” 67-72. It is likely that the cell types expressing these molecules are primarily medullary thymic epithelial cells and cells of the macrophage, dendritic lineage. For instance, with loss of AIRE gene function, insulin message73 disappears from the thymus65. Altering insulin expression in the thymus (e.g. insulin 2 gene knockout in NOD mouse) can have a dramatic effect on development of autoimmunity 74, 74-78 and the protection afforded by the insulin gene 5’VNTR in man is associated with greater thymic insulin message 68, 79. Thus an attractive hypothesis is that mutations of the AIRE gene (e.g. APS-1 syndrome) cause loss of peripheral antigen expression in the thymus80 and probably decreased deletion of autoreactive T lymphocytes that target such peripheral antigens. Of note, peripheral antigens are also expressed within other lymphoid organs81 and AIRE is reported to be functionally relevant in lymph nodes82, 83.

A single family has been described with an autosomal dominant form of the disease (thyroiditis prominent in this family)84, and of note Anderson and colleagues have produced an animal model of the dominant mutation found in this family57. The specific knockin mutation (G228W) of AIRE functioned as a dominant negative, recruiting wild type AIRE away from active sites of transcription, decreased thymic messenger RNA for multiple AIRE regulated thymic genes, and the mice develop lachrymal, salivary, and thyroid infiltrates and progressive peripheral neuropathy. Of note with the mutation on an NOD background diabetes is not accelerated and the mice do not develop pancreatitis (found in NOD mice with homozygous knockouts of AIRE). AIRE presumably acts by altering transcription of multiple thymic genes and has important interaction with chromatin57.

|

Table 8.1. Disease Associations |

|

|

|

Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndrome Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndrome |

|

Type 1 Incidence Type 2 Incidence |

|

|

|

Mucocutaneous candidiasis1, 85 C* Addison’s disease86 C |

|

Addison’s disease1, 85 C |

|

Hypoparathyroidism85 C |

|

Chronic active hepatitis1, 85, 87 C |

|

Graves’ disease I Graves’ disease I |

|

Autoimmune thyroiditis85, 88 I Autoimmune thyroiditis89 I |

|

Pernicious anemia C Pernicious anemia90, 91 C |

|

Vitiligo C Vitiligo90, 92-94 C |

|

Type 1 DM (18%) 1, 85 I Type 1 DM (50%) C |

|

Alopecia33, 95, 96 I Alopecia I |

|

Myasthenia gravis97, 98 I |

|

Malabsorption syndrome30, 85 I Celiac disease, Dermatitis C |

|

herpetiformis99-101 |

|

IgA deficiency I IgA deficiency94 I |

|

Serositis102 R |

|

Asplenism47 C |

|

Ectodermal dysplasia1 C |

|

Keratitis103 C |

|

Hypogonadism34, 85 C Hypogonadism104 I |

|

Stiff-man syndrome105 R |

|

Parkinsons disease I |

|

Dental enamel and nail dystrophy1 C |

|

Idiopathic heart block90 R |

|

Pure red cell aplasia45 R |

|

Idiopathic thrombocytopenia106, 107 I |

|

Hypophysitis108, 109 R |

|

Autoimmune Bronchiolitis110 R |

|

*C=common within syndrome; R=rare; I=intermediate |

Patients with APS-1 express autoantibodies reacting with a remarkable diversity of autoantigens, both autoantibodies specifically only detected in APS-1 patients and autoantibodies found in common isolated examples of the autoimmune disorder (e.g. 21 hydroxylase autoantibodies for Addison’s disease). Kampe and coworkers have recently described the presence of autoantibodies reacting with NALP5 in approximately 50% of patients with APS-1 and hypoparathyroidism, but not found in patients with isolated hypoparathyroidism25. The NALP5 gene is specifically expressed in the parathyroid and ovary. Prospective studies are needed to define when autoantibodies to NALP5 appear and whether they disappear following the development of hypoparathyroidism in a subset of patients, thus correlating with lack of the autoantibodies in approximately 50% of the APS-1 patients with hypoparathyroidism. Why NALP5 should be highly expressed in the parathyroid glands and why they are such a prominent target of autoantibodies in this particular syndrome are unknown. The molecule NALP5 (NACHT leucine-rich-repeat protein 5) is a member of a family of molecules important for activating the innate immune system as part of the inflammasome pathway and are potent activators of interleukin 1111-113. They are involved in processes as diverse as autoinflammatory diseases, the inflammation secondary to the sensing of urate crystals in gout114, and even (NALP3) the adjuvant effects of alum115. A polymorphism of NALP1 has been associated with vitiligo116.

Particular patterns of autoantibodies are associated with APS-1117-119. The presence of anti-adrenal autoantibodies (e.g. 21-hydroxylase) is strongly associated with subsequent development of Addison’s disease. In addition, anti-GAD autoantibodies of patients with the APS I syndrome differ from anti-GAD autoantibodies of typical patients with type 1 diabetes in terms of being able to react with GAD on Western blots and inhibit enzymatic activity. A minority (18%) of patients with APS I develop type 1 diabetes85. Many patients express ICA and anti-GAD autoantibodies [“restricted” ICA (41%)] with relatively little progression to diabetes. Patients expressing multiple anti-islet autoantibodies are at higher risk for progression to diabetes. APS-1 patients express additional autoantibodies consistent with widespread loss of tolerance to multiple self antigens120. A study by Soderbergh and coworkers have analyzed the prevalence of a series of autoantibodies in patients with APS-1121 with for instance IA-2 autoantibodies highly associated with type 1 diabetes, while GAD autoantibodies were more associated with intestinal dysfunction. Hypogonadism was associated with side-chain cleavage enzyme (SCC) while Addison’s disease was associated with both SCC autoantibodies and 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies.

|

Table 8.2. Comparison of APS-1 and APS-2

|

|

APS-I APS-2

|

|

Onset infancy Older onset Siblings affected (autosomal recessive, Multiple generations Chromosome 21, AIRE gene) Not HLA associated but specific disease DR3/DR4 associated Autoantibodies to Type 1 Interferons and Th17 cytokines (IL17A, IL17F, IL22) No autoantibodies to cytokines Asplenism Mucocutaneous candidiasis No defined immunodeficiency |

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of APS-1 is usually made with finding 2 or 3 of the following: mucocutaneous candidiasis, hypoparathyroidism and/or adrenal insufficiency (or autoantibodies against CYP450c21, 21 hydroxylase). It has recently been reported that 100% of patients with APS-1 express autoantibodies reacting with interferon-omega and the great majority express autoantibodies reacting with interferon alpha55, 122. We have developed an ELISA format assay utilizing time resolved fluorescence of Europium to detect autoantibodies and can confirm the very high prevalence of anti-interferon autoantibodies in patients with APS-1122. A commercial hit for such autoantibodies is als abailable from RSR/Kronus. The autoantibodies are apparently the first autoantibodies to develop and remain throughout the disease course, a very remarkable finding. Thus an initial diagnostic screen can be performed for autoantibodies reacting with interferons (a subset of patients with myasthenia gravis and thymoma as well as patients treated with interferons also produce anti-interferon antibodies). Final diagnosis is usually dependent upon direct AIRE gene sequencing, with difficulty arising in defining mutations on both genes in the presence of deletions.

Given that the individual components of disease develop over years to decades, one must be vigilant for other associated autoimmune disorders. Perheentupa recommends that individuals under the age of 30 years with any of the following: chronic or recurring mucocutaneous candidiasis, hypoparathyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, chronic gastrointestinal disease characterized by obstipation, diarrhea or steatorrhea, alopecia, vitiligo, noninfectious hepatitis, keratoconjunctivitis or urticaria-like erythema with fever should be closely evaluated for signs of ectodermal dysplasia and consideration for AIRE gene mutational analysis entertained. If more than one of these components is identified, the individuals should be closely followed for the development of additional disease. Siblings of affected individuals need only have one of the above to warrant more aggressive surveillance 123. Of note, multiple mutations of the AIRE gene have been implicated in the pathogenesis of disease. Therefore, the sensitivity of mutational analysis is dependent upon the number of mutations screened for and the underlying prevalence of the mutations in the population 56.

Surveillance

Once the diagnosis of APS-1 is established, the individuals should be referred to a center with experience following these patients and enrolled in a systematic screening regimen with the goal of identifying developing autoimmune disease prior to significant clinical sequelae are reached. Ideally, these individuals should be evaluated every six months for maintenance of their current endocrine disorders and surveillance for future disorders. Table 8.3 outlines recommended screening tests. Mucocutaneous candidiasis may manifest itself anywhere in the GI tract. Therefore, the organism may be identified from the oral mucosa or stool smears. Individuals with symptoms of dysphasia or chest pain should be evaluated by endoscopy to identify strictures. Of note, sudden hypercalcemia in hypoparathyroid individuals may mark the beginning of adrenal insufficiency and deserves evaluation 124. The gastrointestinal system may be involved (Table 8.4) 48, 49, 123. Symptoms of diarrhea, malabsorption with failure to thrive in children and/or obstipation may be identified. These symptoms maybe due to the underlying endocrine disease (e.g. diarrhea with the hypocalcemia of hypoparathyroidism) or may be a manifestation of a new disorder. Evaluation of these symptoms may require investigation for other autoimmune GI disorders such as pernicious anemia and celiac disease, evaluation for fat malabsorption that may be observed with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and consideration of an autoantibody to endocrine cells of the GI tract (intestinal biopsy often reveals loss of enteroendocrine cells including serotonin expressing cells50), and close consultation with a gastroenterologist is needed. Monitoring for asplenism which can develop over time is also important 42.Table 8.5 lists several conditions that have been rarely identified in individuals with APS-1123.

Treatment

Patient education is a critical element of a successful treatment plan. These individuals often suffer from multiple endocrinopathies and are at risk for the development of further disease. They must be aware of signs and symptoms of new disease and carry with them information about their disease, should emergency care be needed 123. Treatment will in part depend upon the autoimmune disorder identified (table 8.6). Of note, aggressive therapy of oral candidiasis 125 is indicated in an effort to prevent the late complication of epithelial carcinoma. Any lesions that are suspicious should be biopsied 123. Keratoconjunctivitis must also be aggressively treated to prevent a decrease in visual acuity 103. Asplenic individuals are also at risk for fulminant sepsis 126. They must be aggressively identified and immunized for hemophilus influenza, meningococcus and pneumococcus. If the individual mounts an inadequate antibody response, daily antibiotics are indicated, as prophylaxis and emergency care should be sought for fever (table 8.6).

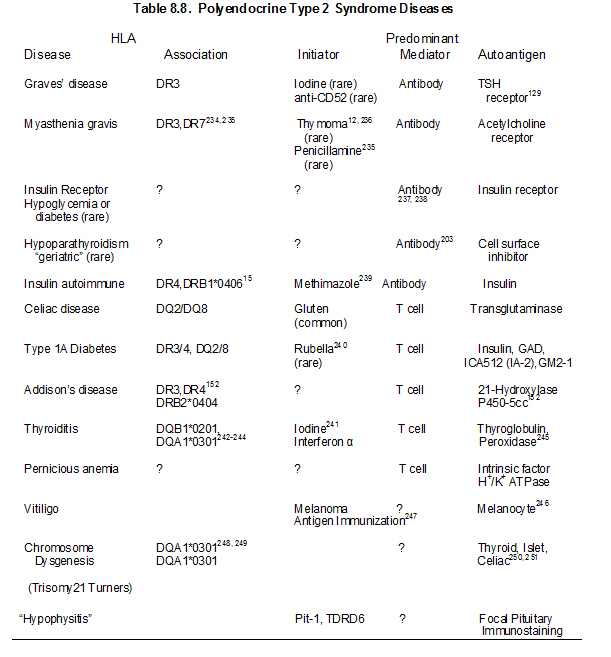

Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndrome Type 2 (APS-2, Schmidt’s Syndrome)

The type 2 syndrome is the most common autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome127. In 1926, Schmidt described two subjects with thyroiditis and Addison’s disease4. Other diseases of the APS 2 include Graves’ disease (thyrotoxicosis), primary hypothyroidism89, insulin-dependent or type 1A diabetes mellitus (IDDM), celiac disease101, 128-130 vitiligo90, 92-94 serositis102, IgA deficiency94, primary hypogonadism104, stiff-man syndrome105, alopecia, pernicious anemia90, 91, myasthenia gravis97, hypopituitarism131, 132 and Parkinson’s disease. Organ-specific autoantibodies in the absence of overt disease is also frequently present in patients and their relatives133. Some authors divide the APS-2 syndrome based upon the specific disease components reserving APS-2 for Addison’s disease plus autoimmune thyroid disease or type 1 diabetes (e.g. APS-3 for thyroid autoimmunity plus other autoimmune (not Addison’s or hypoparathyroidism); APS-4 for two or more other organ specific autoimmune diseases). In that the additional divisions at present provide limited prognostic information (e.g. patient with diabetes and thyroiditis are at risk for Addison’s) we will use APS-2 as inclusive of multiple autoimmune disorders with one or more autoimmune endocrine diseases but distinguished from APS-1 with its unique triad of hypoparathyroidism, mucocutaneous candidiasis and Addison’s disease and identified mutation of the AIRE gene.

There has been a marked increase in knowledge concerning genetic determinants of disorders such as Type 1A diabetes given whole genome screens analyzing thousands of patients and controls134. The predominant locus influencing Addison’s disease with or without other disorders is the MHC135. The majority of the genes influencing susceptibility outside of the major histocompatibility complex have extremely small odds ratios (often less than 1.2) and thus their analysis in relatively uncommon disorders such as APS-2 is problematic. The major polymorphism (PTPN22 or Lymphocyte Specific Phosphatase R620W) one of the strongest type 1A diabetes non-MHC genes136 is associated with Addison’s disease137-140, but the remainder of the other multiple loci have not been studied for Addison’s disease in detail/ have conflicting findings with limited power141-144. With large genome-wide studies of common disorders such as Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis multiple immune related genes (e.g. CTLA4, PTPN22, FCRL3) clearly influence disease with relatively small odds ratios145, 146 with evidence of MHC heterogeneity between Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis145, 147. Loci associated with Addison’s disease outside of the MHC include NALP1 (PR215, minor allele coding SNPrs I2I50220)148 CTLA4-Ala17 (OR = 2.4), Programmed Death Ligand PDLI (OR=1.3)149 and CYP27 (vitamin D I) 150 and vitamin D receptor151.

Genetic abnormalities underlying disease susceptibility for APS-2 and consist primarily of alleles of genes within the major histocompatibility complex. Initial studies associated APS-2 with the class I HLA allele B8 18. HLA-B8 is in linkage dysequilibrium with HLA-DR3, which is in turn is in strong linkage dysequilibrium with DQ2 (DQA1*0501, DQB1*0201). The primary association of APS-2, similar to many autoimmune disorders appears to be with class II HLA alleles (immune response genes) and in particular with DQ2 and DQ8. Thus APS-2 is strongly associated with human leukocyte (HLA) haplotypes with DR3/DQ2 [DQ2:DQA1*0501, DQB1*0201) and DR4/DQ8 (DQ8:DQA1*0301, DQB1*0302) and with DRB1*0404152-154 particularly in the rare multiplex Addison’s disease families) 155-158. A recent study from our group indicates that the association with HLA-B8 is not simply due to its linkage dysequilibrium with DR3-DQ2. In multiplex Addison’s disease families, 95% of DR3 haplotypes have HLA-B8 compared to approximately 50% of control U.S. DR3 haplotypes. The DR3-DQ2-B8 (3.8) of Addison’s disease differs from the usual 3.8.1 (A1) extended haplotype in terms of less often being conserved to A1. This suggests that either B8 itself increases risk or other alleles between DQ and HLA B or B8 itself increases risks and loci between HLA-B and HLA-A decrease Addison’s risk of the 3.8.1 conserved extended haplotype.

Many of the diseases of the type 2 syndrome are associated with HLA antigens HLA-DR3 or HLA-DR4 152, 156, 159 (Table 8.4) Primary adrenal insufficiency in the type 2, but not the type 1 syndrome, is strongly associated with both HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR4152. The association of HLA markers with disease can correlate with inheritance of a common HLA-haplotype within families, but haplotypes with DR3 are often introduced into the family by more than one relative152. Other HLA-B8 and DR3 associated illnesses include selective IgA deficiency160-162 juvenile dermatomyositis, and dermatitis herpetiformis101, alopecia, scleroderma163, autoimmune thrombocytopenia purpura164, hypophysitis108, 109 metaphyseal osteopenia165, and serositis102. A recent report implicates HLA-C as having a greater association with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis than class II HLA alleles, though multiple MHC alleles contribute166.

Several diseases that manifest in patients with polyendocrine autoimmune syndromes are not associated with HLA-B8 or HLA-DR3 in population studies. These disorders include vitiligo167, pernicious anemia61, and autoimmune goitrous thyroiditis168-170. Addison’s disease patients also frequently have DQ8, DQB1*0602, and DR5 associated haplotypes(different from patients with type 1 diabetes)135, 171. In our studies, approximately 30% of patients with Addison’s disease are DR3/4, DQ2/DQ8 heterozygous compared to 2.4% of the general U.S. population. This occurs in the U.S. for patients with or without type 1 diabetes. Between 70 to 80% of DR4 alleles in patients with Addison’s disease have DRB1 allele 0404. This is similar to a national study of Addison’s disease patients in Norway153. Such genotypic associations are likely to vary by country depending on the frequency of specific HLA DR and DQ haplotypes. HLA class I alleles also influence risk171

Another allele of an MHC gene that is associated with Addison’s disease is the “5.1” allele of the atypical class I HLA molecule MIC-A172, 173. The MIC-A5.1 allele has a very strong association with Addison’s disease that is not accounted for by linkage dysequilibrium with DR3 or DR4 172, 174, but with extended haplotypes and association of MICA alleles with HLA-B alleles (5.1 with B8 and MICA5 with HLA B15 may not be a causative gene154. The MICA5.1 association is complicated by the protective association of HLA-B15 for Addison’s disease171 and the tight linkage disequilibrium between MIC-A and HLA B alleles. The MHC class II transactivator gene on chromosome 16 influences expression of class II molecules. A single report indicates association of a polymorphism of this gene with a G allele present in 67% of patients with Addison’s disease (n=128) versus 49% of controls154.

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS

Initiating factors for the type 2 syndrome and its component illnesses are not established except for celiac disease (wheat protein gliadin) 175, the insulin autoimmune syndrome (e.g. methimizole), myasthenia gravis (rarely penicillamine176), type 1A diabetes (rarely congenital rubella), Graves’ disease (rarely anti-CD52 monoclonal treating patients with multiple sclerosis177) and hypothyroidism (interferon therapy associated with thyroid autoimmunity and diabetes)178-182. A patient treated with interferon alpha developed autoimmune thyroid disease, Addison’s disease and premature ovarian failure that resolved with termination of interferon alpha therapy183.Patients with celiac disease, which is characterized by atrophy of intestinal villi associated with lymphocytic infiltration, have autoantibodies reacting with transglutaminase (the endomysial antigen)129 and with less specificity and sensitivity with the wheat protein gliadin. In contrast to the lack of specificity with gliadin antibody assays, assays of antibodies to deamidated gliadin appear highly specific, and respond to removal of gliadin from the diet more rapidly than transglutaminase autoantibodies184. Removal of gliadin from the diet restores intestinal villi to normal185. There is a well developed hypothesis in terms of the pathogenesis of celiac disease with the deamidation of gliadin by transglutaminase leading to increased binding of the deamidated peptide to HLA DQ2 and DQ8 class II molecules and activation of the disease by presentation of the modified peptides to T lymphocytes186.

Controversial data suggest that ingestion of the milk protein bovine albumin in the first few months of life may be associated with type 1 diabetes187 while other investigators implicate casein, and studies from Denver and Germany implicate early (<3 months) ingestion of wheat. A recent study of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid ingestion188 analyzing both dietary history and levels of fatty acids in prospectively obtained red cells associates increased ingestion with decreased risk of developing islet autoimmunity188. These dietary factors appear to increase/decrease risk of islet autoimmunity less than 2-3 fold. A number of drugs are associated with induction of autoimmunity including interferon-a (thyroiditis)189. Remarkably 190, 191 1/3 of multiple sclerosis patients treated with an anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody developed Graves’ disease177. Apparently non-multiple sclerosis patients treated with the same monoclonal do not develop Graves’ disease.

AUTOANTIBODIES

Families with the type 2 polyendocrine syndrome should be evaluated over time to detect the presence of organ-specific antibodies indicating the possibility of a future endocrine malfunction (Table 8.7). All such relatives should be advised of the early symptoms and signs of the principal component diseases. Even though signs and symptoms of disease may be absent, patients with multiple disorders should be screened every few years with measurement of anti-islet antibodies, 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies and transglutaminase autoantibodies, a sensitive thyrotropin assay, and measurement of serum B12 levels192.

Annual ACTH is indicated if 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies are detected152, 194 and then cosyntropin (adrenocorticotropin)-stimulated cortisol determination (cosyntropin test if ACTH is increasing or if symptoms/signs of Addison’s disease are present193). Assays of anti-islet cell antibodies195, 196 anti-thyroid and anti-adrenal antibodies(21-hydroxylase)86, 197-200 and anti-ovarian antibodies104, 201 help identify subjects at increased disease risk. Screening of patients with Type I diabetes for 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies indicates that 1.5% are positive. Approximately 20 percent of APS-2 patients expressing 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies progressed to overt Addison’s disease with long-term follow-up(up to approximately 20 years).193, 202

More than 20 years may elapse between the onset on one endocrinopathy and the diagnosis of the next. As many as 40-50% of subjects with Addison’s disease will develop an associated endocrinopathy. A distinction must be made for subjects with isolated thyroid disease (relatively frequent in the general population) who have no family history of polyglandular syndrome type 2. Such individuals have a relatively low probability of developing additional autoimmune disorders in comparison with individuals with rare autoimmune disorders such as Addison’s disease or myasthenia gravis.

Rarely, hypoparathyroidism, a specific endocrine disturbance present in the type 1 syndrome, is identified in a patient with type 2 syndrome. Hypoparathyroidism in such type 2 polyendocrine autoimmune patients may result from a “suppressive” autoantibody203, 204 rather than the assumed parathyroid destruction as in the type 1 syndrome such as activating antibodies to the calcium receptor 24. Activating antibodies to the calcium receptor appear causative in a subset of patients with hypoparathyroidism24, 205-207 and antibodies to Nalp5 are associated in APS-1 patients25. In a patient with the type 2 syndrome, celiac disease is a more frequent cause of hypocalcemia than hypoparathyroidism.

Several autoantibodies are both disease specific (e.g., anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies in myasthenia gravis208 and anti-TSH receptor antibodies in Graves’ disease209) and causal. “Causal” autoantibodies are associated with transplacental disease transmission. Other autoantibodies (e.g., antithyroid autoantibodies including anti-thyroid peroxidase, formerly termed anti-microsomal, and anti-thyroglobulin) are as frequent among patients and relatives as to be of little predictive value. For example, a relative with anti-thyroid peroxidase autoantibodies has a low risk of hypothyroidism unless evidence of abnormal thyroid function is also present (e.g., elevated TSH). In a similar manner, many individuals may have antibodies to parietal cells, H+/K+ adenosine triphosphatase210 of the stomach211, 212 and intrinsic factor, but the autoantibodies may not correlate well with abnormal gastric acid secretion or development of pernicious anemia61.

In the APS-2 syndrome, many ICA-positive individuals do not progress to diabetes, and diabetes risk is much lower than for ICA-positive first-degree relatives of patients with type 1 diabetes195, 196. These non-progressing ICA-positive polyendocrine patients usually express what has been termed “selective” or restricted ICA195. Such ICA reacts only with islet B cells (insulin producing), not A cells (glucagon producing) within rat islets and fail to react with mouse islets. They represent unusual high titer autoantibodies reacting with glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), which is not expressed at detectable levels in mouse islets. This unusual form of ICA confers a lower risk of type 1 diabetes as compared with nonrestricted ICA (reacts with multiple islet molecules) for both polyendocrine patients and relatives of patients with type 1 diabetes. If multiple anti-islet autoantibodies (of GAD, insulin and IA-2) are present, there is a high risk of diabetes.

|

Table 8.7. Type 1A Diabetes and Polyendocrine Autoimmunity

|

|

· As many as 18% of APS-1 patients become diabetic as do approximately 15% of patients with Addison’s disease (non-APS-I) · “Restricted” or GAD-ICA is common among APS 2 patients with lower risk of progression to diabetes unless IA-2 autoantibodies are present · APS-1 and 2: DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602 Protection from Diabetes · APS-2: Later mean age of diabetes onset than typical type 1A patients · APS-I: Anti-GAD autoantibodies react with GAD on Western blots and inhibit enzymatic activity 213

|

Other autoantibodies associated with the type 2 syndrome include anti-melanocytic, anti-adrenal 60 and anti-gonadal autoantibodies198. Anti-adrenal cortical antibodies have been used to predict adrenal insufficiency in the type 1 syndrome (in particular 21-hydroxylase). In particular amongst patients with 21-hydoxylase autoantibodies, follow up with annual ACTH levels allows early diagnosis193. Addison’s disease is associated with premature ovarian failure and antibodies to steroid cells predictive37. It is noteworthy that many of the polyendocrine autoantibodies react with intracellular enzymes, including thyroid peroxidase (Hashimoto’s thyroiditis), glutamic acid decarboxylase (type 1 diabetes and stiff-man syndrome), 21 hydroxylase (Addison’s disease), and cytochrome P450 cholesterol side chain cleavage enzyme117 (Addison’s disease). In addition, antibodies to hormones can be present, including anti-insulin, anti-thyroxine, and anti-intrinsic factor antibodies (pernicious anemia). It is now relatively easy to develop highly specific and sensitive assays for autoantibodies reacting with in vitro transcription and translation of cDNAs of the relevant protein. The specificity of ELISA format assays can be enhanced with competition with fluid phase molecules and detection with fluorescence assays214. Dr. Hutton and colleagues utilized identification of tissue specificity followed by development of fluid phase radioassay to define the fourth major islet autoantigen, namely the beta cell Zinc transporter(ZnT8)215.

Antibodies to specific receptors are characteristic of given disorders (anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies of myasthenia gravis, anti-TSH receptor antibodies of Graves’ disease or hypothyroidism216, and oocyte sperm receptor autoantibodies associated with oophoritis). The large variety of target molecules, (e.g., type 1 diabetes), presence of high affinity IgG autoantibodies, and the sequential appearance over months or years of specific antibodies or disorders suggest that the production of most autoantibodies is secondary to tissue destruction and are antigen “driven”217.

PATHOGENESIS

A central question is what links all the different disorders of the APS-2 syndrome? Why do some individuals have a single autoimmune disorder while others have multiple diseases?

One hypothesis is that different tissues share the same autoantigen and thus when autoimmunity is directed at one organ it will also affect other organs. This is highly unlikely given the number of different molecules targeted specifically for many autoimmune disorders and the wide discordance in time relative to the appearance of for instance specific autoantibodies and disease. Another hypothesis is that different organs may share immunologically related molecules (mimics) and such mimics may be as simple as short peptides recognized by T lymphocytes. That is also a possibility (see below), but would not explain the wide time differences of disease appearance and spectrum of different illnesses. We believe the most likely link between the diverse diseases is genetic propensity to fail to maintain tolerance to multiple self-molecules, and in particular specific self-peptides. Environmental factors and additional genetic determinants (e.g. specific HLA alleles) then determine the timing of loss of tolerance and the probability that a specific organ will be targeted. For instance, the highest risk (for Type 1 diabetes) HLA genotype DR3-DQ2; DR4-DQ8 is associated with a young age of diabetes onset. Failure to maintain tolerance can be a result of deficient T regulation or enhanced T cell activation. An additional hypothesis is that HLA alleles associated with autoimmunity might be inherently contributing to generalized autoreactivity. We find that hypothesis unattractive in that specific HLA haplotypes can be protective for one autoimmune disorder and promote another. For example DR2/DQB1*0602 haplotypes are high risk for multiple sclerosis but provide dominant protection for type 1A diabetes.

Both autoreactive T cells and autoantibodies can be pathogenic, depending on the specific disease. In Graves’ disease, anti-thyrotropin (TSH) autoantibodies lead to thyroid hyperfunction218 and anti-insulin receptor autoantibodies can result in either hypoglycemia or insulin resistance with hyperglycemia15, 219. Type 1A diabetes is a T cell mediated disorder and an interesting case report describes a child developing diabetes with a mutation eliminating B-lymphocytes and thus autoantibodies (59). Nevertheless, the anti-B cell monoclonal Rituximab (anti-CD20) slowed progression of C-peptide loss in new onset diabetic patients. 220

T cell autoimmunity has been much more difficult to study and correlate with disease compared to autoantibodies. Recent advances in T cell immunobiology, studies of animal models, and transfer of autoreactive T lymphocytes or affected human organs into immunodeficient mice should lead to progress in understanding T cell autoimmunity (See chapter on T lymphocytes). For instance, as expected the 21 hydroxylase molecule is a T cell target in Addison’s disease221, with multiple peptides of 21-hydroxylase presented by HLA-B8 to patient T lymphocytes.

For decades, experimental animal models of organ-specific autoimmunity have been studied. These were dependent upon the injection of putative autoantigens into animals in the presence of adjuvants that enhance inflammation107. Thus, thyroiditis can readily be induced in selective strains of mice following injection of thyroglobulin or thyroid peroxidase in Freund’s adjuvant. Anti-insulin autoantibodies can be induced in normal Balb/c mice following the administration of insulin peptide B:9-23, and these autoantibodies react with intact insulin and are not absorbed by the immunizing peptide222. In Balb/c mice expressing an activating molecule in islets (B7.1) immunization with the B:9-23 peptide leads to diabetes. T cell clones reacting with these molecules, or other selected peptides, are generated, and such clones when transferred into naive animals induce disease. Of note, several forms of immunization with such autoreactive clones can be used to make animals refractory to disease induction223. These studies provide clear evidence that autoreactive T cells are present in normal animals and they can be rapidly activated, given “appropriate” stimulation.

In addition, studies by Tung and associates and Wucherpfennig and colleagues suggests one mechanism whereby properties of T cell recognition may lead to multiple autoimmune disorders107, 224. In studying experimental autoimmune oophoritis, Tang and colleagues identified a peptide of the oocyte sperm receptor (ZP3) that upon injection in adjuvant induced disease. They then identified which of nine amino acids of this peptide were essential to activate autoimmune T cell clones or induce disease. T cells recognize only short peptides presented in the groove of class I or class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules on antigen-presenting cells. As few as three properly spaced amino acids (of nine) interacting with a T cell receptor can be sufficient to trigger T cell responses. Noting that a peptide of the acetylcholine receptor had the appropriate T cell binding motif associated with experimental oophoritis, they demonstrated that this peptide stimulated an oophoritis-derived T cell clone in vitro and when administered in vivo induced oophoritis. The requirement for sharing of as few as three of nine amino acids of a linear sequence for activation of autoreactive T cells provides a mechanism whereby inflammation directed at one organ may spread to additional tissues by T cell cross reactions to distinct peptides of different tissues. Such a model may also help explain disease associations. For example, Graves’ thyroid disease is frequently complicated by autoimmunity directed at extraocular muscles leading to Graves’ ophthalmopathy225. If such a mechanism for the “spreading” of autoimmunity is operative, it implies that mechanisms to suppress autoreactivity are particularly important. The possibilities that “molecular mimicry” may induce autoimmunity are greatly increased if short minimally homologous sequences are sufficient to stimulate cross-reactive T cell clones.

Very important animal models of polyendocrine autoimmunity indicate that loss of regulatory T lymphocytes can result in widespread autoimmunity. These models utilize either neonatal thymectomy or a combination of radiation and immunosuppressive drugs and transfer of T cell subsets to immunodeficient mice to induce autoimmunity 226-232. The general concept is that within the thymus, early in development, a subset of essential regulatory T lymphocytes develops and seeds the periphery. Interference with this normal mechanism results in loss of tolerance to multiple molecules, and thus multiple organs are the target of autoimmunity. This is a rapidly developing field. The IPEX syndrome (see below) with its fatal neonatal autoimmunity and loss of a key regulatory molecule (Foxp3) illustrates how this concept can apply to human autoimmune disorders233.

Kriegel and co-workers reported that patients with APS-2 have a defect in terms of lymphocyte response to CD4+CD25+ T cell suppression 252. Interruption of normal T cell development can result in multiple autoimmune disorders. The BB rat develops type 1 diabetes and thyroiditis in association with a severe T cell immunodeficiency253. Neonatal thymectomy induces autoimmunity apparently by removing regulatory T cells254, 255. A series of different regulatory T cells (e.g. CD4+CD25+, NK T cells) are now the subject of intense investigation 256. Of note the Foxp3 molecule is essential for regulatory T lymphocytes and when it is mutated (IPEX syndrome-see below) neonatal autoimmune diabetes results257, 258.

Autoimmune disorders appear to share a number of “non-specific” abnormalities of T cell function or enumeration including increased numbers of cells expressing class II molecules (“Ia” positive T cells)259, IL2 receptors, depressed autologous mixed lymphocyte responses260, and lack of NK T cells261. Studies of NK T cells in man are controversial with tetramer analysis not confirming decreased numbers in patients with type 1A diabetes, but rather stable wide variation in the percentage of such cells between even normal individuals262. The above abnormalities appear not to be disease specific and may relate to fundamental abnormalities predisposing to autoimmunity or reflect disease activity.

IDENTIFICATION OF CASES

Individuals with a single autoimmune disease are at increased risk for the development of a second disease compared to the general population. Table 8.9 shows the prevalence of autoimmune endocrine disease in the general population and the co-incidence of a second autoimmune disease given that a first exists. In addition, individuals with APS-2 syndrome will often develop autoimmunity sequentially over the time course of many years. An individual often will not have polyglandular failure at the onset of clinical symptoms of the initial autoimmune disease. Therefore, a high clinical suspicion for the development of sequential autoimmune diseases must be maintained 263. Specific screening strategies depend on the presenting autoimmune disease. Significant controversy exists regarding the screening tests that should be employed and the frequency of testing performed. For example, in type 1 diabetes, it is generally accepted that routine screening for thyroid disease with biochemical assays should be performed (e.g. TSH assay), through the frequency of this screening is a source of controversy 264; 265. Even more controversial is the screening for celiac disease in this population. While the elevated risk of celiac disease in the diabetic population has been well established 129, 266-267, many of these individuals are asymptomatic at the time of identification and the long term sequelae of untreated asymptomatic celiac disease in regards to growth, pubertal development, bone mineralization and gastrointestinal malignancy is unclear. To avoid “negative” celiac intestinal biopsies, we refer for biopsy primarily patients with high levels of transglutaminase autoantibodies. Increased levels of transglutaminase autoantibodies are strongly associated with a positive celiac biopsy268. The appropriate level is assay specific. For the fluid phase radioassay we utilize, an index of 0.05 represents the 99th percentile of normal controls while a level of 0.5 is the cutoff we utilize for obtaining biopsy.

Studies of anti-pituitary (anti-hypothalmic)269 autoimmunity have progressed in the past decade270, 271 including identification of IgG4 hypophysitis271, anti-Pit1 combined pituitary deficiencies272 and description of predictive pituitary antibody staining pattern131. Bellastella and coworkers have reported that 99 of 700 of APS patients (primarily patients with thyroid autoimmunity type 1 diabetes mellitus and gastritis) had autoantibodies reacting with isolated pituitary cells (not a diffuse staining pattern)131. Despite normal MRI with 5 years of follow up, 19% with this immunostaining pattern developed one or more pituitary hormone deficiency. Patients with diffuse pituitary antibody staining did not develop hypopituitarism.

Tests may include functional biochemical assays and/or serologic studies to identify organ specific autoantibodies. Once a second autoimmune disease is identified more extensive screening is indicated to identify further disease at an early stage. Screening with autoantibodies associated with diabetes (IA-2, insulin and GAD), thyroid disease (TG and/or TPO), Addison’s disease (21-hydroxylase), celiac disease (transglutaminase) and autoimmune hepatitis (cytochrome P450 enzymes) in addition to biochemical screening with TSH, free T4, FSH, LH, CBC, and electrolytes may uncover occult autoimmune disease.

Therapy

The therapy of the APS-2 syndrome depends upon the specific disease manifestation with a few caveats273. Patients with suspected Addison’s disease and hypothyroidism should be evaluated and treated for adrenal insufficiency prior to replacement of thyroid hormone to avoid Addisonian crisis. There is one fascinating case report of a patient with 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies treated for Graves’ eye disease with a 6 month course of glucocorticoids. In this patient 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies became negative and adrenal function was restored to normal. This remission was reported to have lasted for 100 months at last follow up274.

There are a large number of new potent immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory therapies being used in non-endocrine autoimmune diseases and in various stages of clinical development. Rituximab (anti-CD20 antibody) is one of the more interesting having dramatic effects in multiple sclerosis, transient slowing of loss of c-peptide in patients with new onset diabetes275, 276 and a case report of response of an APS-1 patient with pulmonary disease36 as well as a relatively large clinical experience for the treatment of B-cell lymphomas. In the NOD mouse model of type 1 diabetes anti-CD20 prevents development of diabetes277 and a clinical trial in new onset patients (Trialnet) indicates a single course slows but does not permanently arrest loss of C-peptide. Treatment with rituximab induces long-term B cell depletion, but the antibody does not bind to plasma cells, and often has relatively minor effects on autoantibody levels. It may act by influencing presentation of autoantigens by B-lymphocytes or altering B cell regulation. Studies in Graves’ disease suggest a potential role, but also potential complications 278-280. Trials of modified anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies in new onset type 1 diabetes are very advanced with the potential that such antibodies induce regulatory T lymphocytes as well as acutely and transiently depleting T lymphocytes 281-286. A long-term goal is the development of antigen specific therapy for each of the major autoimmune disorders. In experimental animals regulatory T lymphocytes targeting for instance islet specific molecules can effectively block development of disease287, 288.

IPEX (Immune Dysfunction Polyendocrinopathy X-linked)

The IPEX syndrome presents in neonates with fatal autoimmunity and this very rare disorder has multiple different names reflecting endocrinopathy, allergic manifestations, intestinal destruction and immune dysregulation (e.g. XLAAD: X-Linked Autoimmunity Allergic-Dysregulation Syndrome or XPID, MIM number 304790 and 300292). Children with the disorder can die in infancy and many die in the first days of life but there is heterogeneity with some children surviving 12-15 years233. They manifest neonatal type 1 diabetes, but the cause of death probably relates to massive intestinal involvement and malabsorption. Eighty percent of patients with the IPEX syndrome develop type 1 diabetes. This suggests that in the absence of regulatory T lymphocytes most humans will target and destroy beta cells.289

The disease results from mutations that inactivate the Foxp3 transcription factor and the same gene is also mutated in a mouse model (the Scurfy mouse)6. The pathway this gene controls in T lymphocytes is now identified as central to basic immunology. In particular the gene controls the regulatory function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T lymphocytes. 227, 290 From this discovery it is now apparent why bone marrow transplantation of normal lymphocytes is able to cure the mouse disease, namely the replacement of regulatory lymphocytes is able to control autoimmune reactivity of effector lymphocytes of the Scurfy mouse recipient, despite their lacking the Foxp3 gene.

In that the mouse model is cured with bone marrow transplantation, such therapy has recently been tested in children with the disorder. A child became chimeric after bone marrow transplantation and a remarkable two-year remission was induced(142), followed by an unusual hematological disease that resulted in death. Partial lymphoid chimerism following bone marrow transplantation can induce remission 291. There are now multiple reports of bone marrow transplantation 291-293 and a report of therapy with Sirolimus294.

Anti-Insulin Receptor Antibodies

The presence of anti-insulin receptor autoantibodies is characterized by marked insulin resistance, but paradoxically, patients can also have severe hypoglycemia9. Approximately one third of the subjects have other autoimmune disorders. Characteristically, associated autoimmune diseases are non-organ specific295-297. A recent intramural NIH study indicates that a regimen of Rituximab, cyclophosphamide and pulse steroids can induce remission of the disease298.

Thymic Tumors

Thymomas and thymic hyperplasia are associated with a series of autoimmune diseases10-12, 299-301. The most common autoimmune diseases are myasthenia gravis and red cell aplasia302, 303. Graves’ disease, type 1 diabetes, and Addison’s disease may also be associated with thymic tumors. Patients with myasthenia gravis and alopecia totalis are reported to have thymoma 304. Unique anti-acetylcholine receptor autoantibodies may be present with thymoma301 and disease may be initiated by transcription of molecules within the tumor related to acetylcholine receptors305. There is a 1997 report of treatment of a patient with thymoma and pure red cell aplasia with octreotide and prednisone299. Many thymomas lack AIRE expression within the thymoma a potential factor in the development of autoimmunity306, 307. Of note, the one other disease with “frequent” development of anti-cytokine (e.g. anti-inferon and ILI7 (autoantibodies besides AIRE mutations are thymoma associated308). A patient described by Anderson and coworkers with thymoma had acquired polyglandular syndrome and AIRE defect13.

POEMS Syndrome

POEMS (Polyneuropathy, Organomegaly, Endocrinopathy, M-protein, Skin changes) patients usually present with a sensory motor polyneuropathy, diabetes mellitus (50%), primary gonadal failure (70%), and a plasma cell dyscrasia with sclerotic bony lesions309 17, 310. Temporary remission may result following radiotherapy directed at the plasmacytoma and peripheral blood stem cell transplantation has been utilized 311. The syndrome is assumed to be secondary to circulating immunoglobulins but patients have excess vascular endothelial growth factor312, 313 as well as elevated IL1-b, IL-6, and TNF-a310. There is a case report of a presumptive patient with POEMS without polyneuropathy314. A small series of patients have been treated with thalidomide with decrease in VEGF315. A number of centers have extensive experience with autologous stem cell transplantation{26986}{26987}.

Insulin Autoimmune Syndrome (Hirata Syndrome)

The insulin autoimmune syndrome, associated with Graves’ disease and methimazole therapy (or other sulfhydryl containing medications) is of particular interest due to a remarkably strong association with a specific HLA haplotype 15. Such patients with elevated titers of anti-insulin autoantibodies frequently present with hypoglycemia. The disease in Japan is essentially confined to DR4-positive individuals with DRB1*0406239. Even a Portuguese patient with the syndrome had DRB1*0406316. In Hirata syndrome the anti-insulin autoantibodies are polyclonal. Some patients have monoclonal anti-insulin autoantibodies that also induce hypoglycemia and for these patients there is not an HLA association316.

Adult combined Pituitary Hormone Deficiency (CPHD) with Anti-Pit1 Autoantibodies

Yamamoto and coworkers recently described three patients with multiple autoimmune disorders and GH, prolactin and TSH deficiency. In that Pit-1 is a transcription factor essential for production of these pituitary hormones they searched for and found specifically in these three patients autoantibodies to pit-1. In addition, one of the patients with the anti-Pit 1 autoantibodies, lacked pituitary cells producing these hormones272.

Other Disorders

Other diseases with polyendocrine manifestations are Kearns-Sayre syndrome317 diabetes and thyroiditis associated with trisomy 21318, DIDMOAD syndrome (diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy, and nerve deafness, also termed Wolfram syndrome)319-321 and congenital rubella240, 322, 323 associated with thyroiditis and/or diabetes.

The Kearns-Sayre syndrome is characterized by onset before age 20, external ophthalmoplegia, pigmentary retinal degeneration, and one or more of ataxia, heart block, or high cerebrospinal fluid protein. A number of these patients have Hashimoto’s thyroiditis with the suggestion that hypothyroidism is associated with encephalopathy 324, hypoparathyroidism325 and diabetes mellitus and adrenal insufficiency326. The disorder is associated with multiple large-scale327 deletions as well as mutations of mitochondrial DNA 328.

Wolfram syndrome (DIDMOAD syndrome) is characterized by optic atrophy and childhood onset diabetes but the diabetes is not of autoimmune etiology. The gene mutated (wolframin on chromosome 4p16) encodes a glycosylated transmembrane protein of unknown function319, 329 that is localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and may function to limit ER-stress induced cell death 330.

Diabetes develops in a significant number of adolescents and young adults with a history of congenital rubella infection. These patients frequently have thyroiditis, and despite the development of childhood diabetes infrequently express anti-islet autoantibodies 331. Karounos and coworkers have described a rubella protein with homology to an islet protein, suggesting that molecular mimicry may initiate disease332. An alternative hypothesis has been proposed by Rabinowe and coworkers323. They described long-term T cell subset abnormalities in patients following congenital rubella infection.

Conclusions

Polyendocrine autoimmune syndromes have played an important role in understanding autoimmune disorders and in particular type 1A diabetes. The initial evidence that type 1A diabetes was an autoimmune disorder came from its association with spontaneous Addison’s disease, and lack of association with tuberculous Addison’s disease5. The first demonstration of cytoplasmic islet cell autoantibodies occurred in patients with polyendocrine autoimmunity333.

The existence of families of related autoimmune disorders is not only clinically important but also suggests that these diseases are pathogenically related. This relationship probably is a result of two distinct phenomena. The first is inherited abnormalities of immune function, predisposing to the loss of tolerance to a series of self-antigens. The IPEX syndrome with lack of CD4-CD25 regulatory T cells is very instructive with 80% of such children developing type 1 diabetes. Given such a predisposition, “normal” alleles of HLA genes within the major histocompatibility complex may then lead to targeting of specific organs. The second phenomenon that may link these disorders, especially for tightly linked diseases such as Graves’ ophthalmopathy and Graves’ thyroid disease, is creation of pathogenic T or B 334 cells reacting with components of more than one tissue. In that T cell clones can respond to peptides that share no identical amino acids 335, depending upon their three dimensional structure, the potential for such T-cell cross-reactivity must be enormous 334.

Finally, the relationships between these diverse disorders suggest that as disease pathogenesis is elucidated and antigen-specific therapies are developed, the improved understanding of pathogenesis and improvements in therapy will be applicable to many autoimmune diseases.

Reference List

(1) Ahonen P, Myllarniemi S, Sipila I, Perheentupa J. Clinical variation of autoimmune polyendocrinopathy - candidiasis - ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) in a series of 68 patients. N Engl J Med 1990;322(26):1829-36.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=pubmed&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=AbstractPlus&list_uids=2348835&query_hl=4&itool=pubmed_docsum

(2) Betterle C, Ghizzoni L, Cassio A, Baronio F, Cervato S, Garelli S, et al. Autoimmune-Polyendocrinopathy-Candidiasis-Ectodermal- Dystrophy (APECED) in Calabria: clinical, immunological and genetic patterns. J Endocrinol Invest 2011 Nov 21.PM:22104652

(3) Meloni A, Willcox N, Meager A, Atzeni M, Wolff AS, Husebye ES, et al. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1: an extensive longitudinal study in Sardinian patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012 Apr;97(4):1114-24.PM:22344197

(4) Schmidt MB. Eine biglandulare Erkrankung (Nebennieren und Schilddruse) bei Morbus Addisonii. Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol 1926;21:212-21

(5) Nerup J. Addison's disease - clinical studies: A report of 108 cases. Acta Endocrinol 1974;76:127-41.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=4609691&query_hl=5

(6) Patel DD. Escape from tolerance in the human X-linked autoimmunity-allergic disregulation syndrome and the Scurfy mouse. J Clin Invest 2001;107(2):155-7.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=11160129&query_hl=7

(7) Husebye ES, Anderson MS. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes: clues to type 1 diabetes pathogenesis. Immunity 2010 Apr 23;32(4):479-87.PM:20412758

(8) Flier JS, Kahn CR, Roth J, Bar RS. Antibodies that impair insulin receptor binding in an unusual diabetic syndrome with severe insulin resistance. Science 1975;190:63-5.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=170678

(9) Flier JS, Bar RS, Muggeo M, Kahn CR, Roth J, Gorden P. The evolving clinical course of patients with insulin receptor autoantibodies: Spontaneous remission or receptor proliferation with hypoglycemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1978;47:985-95.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=263346

(10) Souadjian JV, Enriquez P, Silverstein MN, Pepin J-M. The spectrum of diseases associated with thymoma. Arch Intern Med 1974;134:374-9.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=4602050

(11) Combs RM. Malignant thymoma, hyperthyroidism and immune disorder. South Med J 1968;61:337-41.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=5644070

(12) Maggi G, Casadio C, Cavallo A, Cianci R, Molinatti M, Ruffini E. Thymoma: results of 241 operated cases. Ann Thorac Surg 1991;51:152-6.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=1985561

(13) Cheng MH, Fan U, Grewal N, Barnes M, Mehta A, Taylor S, et al. Acquired autoimmune polyglandular syndrome, thymoma, and an AIRE defect. N Engl J Med 2010 Feb 25;362(8):764-6.PM:20181983

(14) Hirata Y, Ishizu H, Ouchi N, Motumura S, Abe M, Hara Y, et al. Insulin autoimmunity in a case with spontaneous hypoglycaemia. Japan J Diabetes 1970;13:312-9

(15) Uchigata Y, Hirata Y. Insulin Autoimmune Syndrome (IAS, Hirata Disease). In: Eisenbarth G, editor. Molecular Mechanisms of Endocrine and Organ Specific Autoimmunity.Austin, Texas: R.G.Landes; 1999. p. 133-48.

(16) Imawari M, Akatsuka N, Ishibashi M, Beppu H, Suzuki H, Yoshitoshi Y. Syndrome of plasma cell dyscrasia, polyneuropathy, and endocrine disturbances. Ann Intern Med 1974;81:490-3.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=4416017

(17) Miralles GD, O'Fallon JR, Talley NJ. Plasma-cell dyscrasia with polyneuropathy: the spectrum of POEMS syndrome. N Engl J Med 1992;327(27):1919-23.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=1333569

(18) Eisenbarth GS, Wilson P, Ward F, Lebovitz HE. HLA type and occurrence of disease in familial polyglandular failure. N Engl J Med 1978;298(2):92-4.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/619238?ordinalpos=10&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum

(19) Perheentupa J. Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006 Aug;91(8):2843-50.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16684821?ordinalpos=4&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum

(20) Betterle C. Parathyroid and autoimmunity. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2006 Apr;67(2):147-54.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16639366?ordinalpos=7&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum

(21) Eisenbarth GS, Gottlieb PA. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes. N Engl J Med 2004 May 13;350(20):2068-79.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=pubmed&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=AbstractPlus&list_uids=15141045&query_hl=3&itool=pubmed_docsum

(22) Mathis D, Benoist C. A decade of AIRE. Nat Rev Immunol 2007 Aug;7(8):645-50.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17641664?dopt=Citation

(23) Tomar N, Kaushal E, Das M, Gupta N, Betterle C, Goswami R. Prevalence and significance of NALP5 autoantibodies in patients with idiopathic hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012 Apr;97(4):1219-26.PM:22278434

(24) Gavalas NG, Kemp EH, Krohn KJ, Brown EM, Watson PF, Weetman AP. The calcium-sensing receptor is a target of autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007 Jun;92(6):2107-14

(25) Alimohammadi M, Bjorklund P, Hallgren A, Pontynen N, Szinnai G, Shikama N, et al. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 and NALP5, a parathyroid autoantigen. N Engl J Med 2008 Mar 6;358(10):1018-28.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18322283?ordinalpos=2&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum

(26) Ahlgren KM, Moretti S, Lundgren BA, Karlsson I, Ahlin E, Norling A, et al. Increased IL-17A secretion in response to Candida albicans in autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 and its animal model. Eur J Immunol 2011 Jan;41(1):235-45.PM:21182094

(27) Cludts I, Meager A, Thorpe R, Wadhwa M. Detection of neutralizing interleukin-17 antibodies in autoimmune polyendocrinopathy syndrome-1 (APS-1) patients using a novel non-cell based electrochemiluminescence assay. Cytokine 2010 May;50(2):129-37.PM:20116277

(28) Kisand K, Lilic D, Casanova JL, Peterson P, Meager A, Willcox N. Mucocutaneous candidiasis and autoimmunity against cytokines in APECED and thymoma patients: clinical and pathogenetic implications. Eur J Immunol 2011 Jun;41(6):1517-27.PM:21574164

(29) Bialkowska J, Zygmunt A, Lewinski A, Stankiewicz W, Knopik-Dabrowicz A, Szubert W, et al. Hepatitis and the polyglandular autoimmune syndrome, type 1. Arch Med Sci 2011 Jun;7(3):536-9.PM:22312376

(30) Ekwall O, Sjoberg K, Mirakian R, Rorsman F, Kampe O. Tryptophan hydroxylase autoantibodies and intestinal disease in autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 [letter]. Lancet 1999 Aug 14;354(9178):568.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=10470707

(31) Posovszky C, Lahr G, von SJ, Buderus S, Findeisen A, Schroder C, et al. Loss of enteroendocrine cells in autoimmune-polyendocrine-candidiasis-ectodermal-dystrophy (APECED) syndrome with gastrointestinal dysfunction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012 Feb;97(2):E292-E300.PM:22162465

(32) Oliva-Hemker M, Berkenblit GV, Anhalt GJ, Yardley JH. Pernicious anemia and widespread absence of gastrointestinal endocrine cells in a patient with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type I and malabsorption. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006 Aug;91(8):2833-8

(33) Garty BZ, Kauli R. Alopecia universalis in autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type I. West J Med 1990;152:76-7.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=2309482

(34) Ahonen P, Miettinen A, Perheentupa J. Adrenal and steroidal cell antibodies in patients with autoimmune polyglandular disease type I and risk of adrenocortical and ovarian failure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1987;64(3):494-500.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=3818889

(35) De Luca F, Valenzise M, Alaggio R, Arrigo T, Crisafulli G, Salzano G, et al. Sicilian family with autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) and lethal lung disease in one of the affected brothers. Eur J Pediatr 2008 Feb 15;.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18274776?ordinalpos=29&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum

(36) Popler J, Alimohammadi M, Kampe O, Dalin F, Dishop MK, Barker JM, et al. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1: Utility of KCNRG autoantibodies as a marker of active pulmonary disease and successful treatment with rituximab. Pediatr Pulmonol 2012 Jan;47(1):84-7.PM:21901851

(37) Reato G, Morlin L, Chen S, Furmaniak J, Rees SB, Masiero S, et al. Premature Ovarian Failure in Patients with Autoimmune Addison's Disease: Clinical, Genetic, and Immunological Evaluation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011 Jun 15.PM:21677034

(38) Cakir ED, Ozdemir O, Eren E, Saglam H, Okan M, Tarim OF. Resolution of autoimmune oophoritis after thymectomy in a myasthenia gravis patient. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 2011;3(4):212-5.PM:22155465

(39) Alkaabi JM, Chik CL, Lewanczuk RZ. Pericarditis with cardiac tamponade and addisonian crisis as the presenting features of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type II: a case series. Endocr Pract 2008 May;14(4):474-8

(40) Berger JR, Weaver A, Greenlee J, Wahlen GE. Neurologic consequences of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1. Neurology 2008 Jun 3;70(23):2248-51

(41) Solimena M, De Camilli P. From Th1 to Th2: diabetes immunotherapy shifts gears. Nat Med 1996;2:1311-2

(42) Pollak U, Bar-Sever Z, Hoffer V, Marcus N, Scheuerman O, Garty BZ. Asplenia and functional hyposplenism in autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1. Eur J Pediatr 2008 May 22;.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18496713?ordinalpos=1&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum

(43) Rosa DD, Pasqualotto AC, Denning DW. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and oesophageal cancer. Med Mycol 2008 Feb;46(1):85-91

(44) Valenzise M, Meloni A, Betterle C, Giometto B, Autunno M, Mazzeo A, et al. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy as a possible novel component of autoimmune poly-endocrine-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy. Eur J Pediatr 2008 May 7;.

(45) Mandel M, Etzioni A, Theodor R, Passwell JH. Pure red cell hypoplasia associated with polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type I. Isr J Med Sci 1989;25:138-41.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=2496049

(46) Hara T, Mizuno Y, Nagata M, Okabe Y, Taniguchi S, Harada M, et al. Human gamma delta T-cell receptor-positive cell-mediated inhibition of erythropoiesis in vitro in a patient with type I autoimmune polyglandular syndrome and pure red blood cell aplasia. Blood 1990;75:941-50.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=2105751

(47) Friedman TC, Thomas PM, Fleisher TA, Feuillan P, Parker RI, Cassorla F, et al. Frequent occurrence of asplenism and cholelithiasis in patients with autoimmune polyglandular disease type I. Am J Med 1991;91:625-30.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=1750432

(48) Hogenauer C, Meyer RL, Netto GJ, Bell D, Little KH, Ferries L, et al. Malabsorption due to cholecystokinin deficiency in a patient with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type I. N Engl J Med 2001 Jan 25;344(4):270-4.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=11172154

(49) Gianani R, Eisenbarth GS. Autoimmunity to gastrointestinal endocrine cells in autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003 Apr;88(4):1442-4.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=12679419

(50) Posovszky C, Lahr G, von SJ, Buderus S, Findeisen A, Schroder C, et al. Loss of enteroendocrine cells in autoimmune-polyendocrine-candidiasis-ectodermal-dystrophy (APECED) syndrome with gastrointestinal dysfunction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012 Feb;97(2):E292-E300.PM:22162465

(51) Skoldberg F, Portela-Gomes GM, Grimelius L, Nilsson G, Perheentupa J, Betterle C, et al. Histidine decarboxylase, a pyridoxal phosphate-dependent enzyme, is an autoantigen of gastric enterochromaffin-like cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003 Apr;88(4):1445-52.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12679420?ordinalpos=2&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum

(52) Korniszewski L, Kurzyna M, Stolarski B, Torbicki A, Smerdel A, Ploski R. Fatal primary pulmonary hypertension in a 30-yr-old female with APECED syndrome. Eur Respir J 2003 Oct;22(4):709-11.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14582926?ordinalpos=2&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum

(53) Puel A, Doffinger R, Natividad A, Chrabieh M, Barcenas-Morales G, Picard C, et al. Autoantibodies against IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I. J Exp Med 2010 Feb 15;207(2):291-7.PM:20123958

(54) Kisand K, Boe Wolff AS, Podkrajsek KT, Tserel L, Link M, Kisand KV, et al. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in APECED or thymoma patients correlates with autoimmunity to Th17-associated cytokines. J Exp Med 2010 Feb 15;207(2):299-308.PM:20123959

(55) Meager A, Visvalingam K, Peterson P, Moll K, Murumagi A, Krohn K, et al. Anti-Interferon Autoantibodies in Autoimmune Polyendocrinopathy Syndrome Type 1. PLoS Med 2006 Jun 13;3(7):e289.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16784312?ordinalpos=2&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum

(56) Kumar PG, Laloraya M, She JX. Population genetics and functions of the autoimmune regulator (AIRE). Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2002 Jun;31(2):321-38, vi.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=12092453

(57) Su MA, Giang K, Zumer K, Jiang H, Oven I, Rinn JL, et al. Mechanisms of an autoimmunity syndrome in mice caused by a dominant mutation in Aire. J Clin Invest 2008 May;118(5):1712-26.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18414681?ordinalpos=1&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum

(58) Aaltonen J, Björses P, Sandkuijl L, Perheentupa J, Peltonen L. An autosomal locus causing autoimmune disease: autoimmune polyglandular disease type I assigned to chromosome 21. Nat Genet 1994 Sep;8(1):83-7.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=7987397

(59) Aaltonen J, Björses P, Perheentupa J, Horelli-Kuitunen N, Palotie A, Peltonen L, et al. An autoimmune disease, APECED, caused by mutations in a novel gene featuring two PHD-type zinc-finger domains. Nat Genet 1997;17(4):399-403

(60) Myhre AG, Halonen M, Eskelin P, Ekwall O, Hedstrand H, Rorsman F, et al. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 (APS I) in Norway. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001 Feb;54(2):211-7.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=11207636

(61) Petite J, Rosset N, Chapuis B, Jeannet M. Genetic factors predisposing to autoimmune diseases. Study of HLA antigens in a family with pernicious anemia and thyroid diseases. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1987;117(50):2032-7.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=3433088

(62) Cavadini P, Vermi W, Facchetti F, Fontana S, Nagafuchi S, Mazzolari E, et al. AIRE deficiency in thymus of 2 patients with Omenn syndrome. J Clin Invest 2005 Mar;115(3):728-32.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=15696198

(63) Halonen M, Eskelin P, Myhre AG, Perheentupa J, Husebye ES, Kampe O, et al. AIRE Mutations and Human Leukocyte Antigen Genotypes as Determinants of the Autoimmune Polyendocrinopathy-Candidiasis-Ectodermal Dystrophy Phenotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002 Jun;87(6):2568-74.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=12050215

(64) Ramsey C, Winqvist O, Puhakka L, Halonen M, Moro A, Kampe O, et al. Aire deficient mice develop multiple features of APECED phenotype and show altered immune response. Hum Mol Genet 2002 Feb 15;11(4):397-409.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=11854172

(65) Anderson MS, Venanzi ES, Klein L, Chen Z, Berzins SP, Turley SJ, et al. Projection of an immunological self shadow within the thymus by the aire protein. Science 2002 Nov 15;298(5597):1395-401.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=12376594

(66) Hanahan D. Peripheral-antigen-expressing cells in thymic medulla: factors in self- tolerance and autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol 1998 Dec;10(6):656-62.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=9914224

(67) Heath VL, Moore NC, Parnell SM, Mason DW. Intrathymic expression of genes involved in organ specific autoimmune disease. J Autoimmun 1998 Aug;11(4):309-18.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=9776708

(68) Vafiadis P, Bennett ST, Todd JA, Nadeau J, Grabs R, Goodyer CG, et al. Insulin expression in human thymus is modulated by INS VNTR alleles at the IDDM2 locus. Nat Genet 1997;15:289-92.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=9054944

(69) Pugliese A, Zeller M, Fernandez A, Zalcberg LJ, Bartlett RJ, Ricordi C, et al. The insulin gene is transcribed in the human thymus and transcription levels correlate with allelic variation at the INS VNTR-IDDM2 susceptibility locus for type I diabetes. Nat Genet 1997;15(3):293-7.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=9054945

(70) Chentoufi AA, Polychronakos C. Insulin expression levels in the thymus modulate insulin-specific autoreactive T-cell tolerance: the mechanism by which the IDDM2 locus may predispose to diabetes. diab 2002 May;51(5):1383-90.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=11978634

(71) Pugliese A, Miceli D. The insulin gene in diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2002 Jan;18(1):13-25.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=11921414

(72) Pugliese A. Peripheral antigen-expressing cells and autoimmunity. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 31 ed. W.B. Saunders; 2002. p. 411-30.

(73) Taubert R, Schwendemann J, Kyewski B. Highly variable expression of tissue-restricted self-antigens in human thymus: Implications for self-tolerance and autoimmunity. Eur J Immunol 2007 Mar;37(3):838-48.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=pubmed&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=AbstractPlus&list_uids=17323415&query_hl=1&itool=pubmed_docsum